La scienza dello yoga: il nervo vago

Scienza dello yoga: il nervo vago

ITALIANO

Lo yoga funziona. Su questo non ho dubbi.

A volte ho allievi che dopo una settimana di pratica intensa con me durante un ritiro sono in grado di alleviare dolori che né la medicina tradizionale, né la fisioterapia erano riusciti a mitigare.

Dunque, lo yoga funziona, ma come esattamente? Nel mondo dello yoga, tanti concetti sono tramandati tradizionalmente o per via orale o scritta in modo abbastanza criptico e poco comprensibile. In realtà, vi sono spiegazioni scientifiche che ci aiutano a capire perché lo yoga è così benefico. E con yoga intendo un approccio completo comprendente asana, meditazione e pranayama, non solo la parte fisica. Uno di questi “elementi scientifici” utili è il nervo vago. Ogni pratica yoga, in un modo o in un altro, stimola il tono vagale. Ci sono alcune pratiche più adatte di altre, ma nella stragrande maggioranza dei casi, lo yoga aiuta a favorire il tono vagale.

Iniziamo con un po’ di anatomia. Il nervo vago è uno dei più lunghi, origina nel cervello e, come il suo nome lo indica, vaga un po’ per tutto il corpo. Fa parte del sistema nervoso parasimpatico (“rest and digest”, il sistema nervoso che ci fa sentire calmi, rilassati e tranquilli) e il 20% delle sue fibre controllano gli organi che mantengono in vita il corpo (cuore, digestione, respirazione, ghiandole endocrine), mentre il restate 80% è responsabile della comunicazione tra la pancia/lo stomaco e il cervello. È dunque responsabile della trasmissione di tutte le sensazioni intuitive e le reazioni “di pancia”.

Quando il nervo vago non ha il “tono giusto” molti organi del nostro corpo e addirittura la nostra mente possono essere fuori equilibrio. Si imputa alla mancanza di tono vagale una serie lunga di patologie che parte dal mal di testa, dalla stanchezza e arriva a problemi gastro-intestinali fino alla depressione, agli stati di ansia e ai disturbi alimentari. Sembra quasi assurdo che un solo nervo possa essere responsabile, o in parte responsabile, di così tante patologie.

Recentemente sono stati eseguiti e pubblicati sempre più studi* che cercano di spiegare scientificamente come e perché lo yoga “funziona” e molti sono giunti a un rapporto tra la pratica yoga e il lo stimolo del tono vagale. L’interessante conclusione è che lo yoga, più di altre attività fisiche, aumenta il tono vagale. Il tono vagale è aumentato anche da molti altri fattori, per esempio cantare, ballare, pregare, ridere, ricevere massaggi ma anche per esempio tramite il freddo e il digiuno. Sono elementi molto interessanti che mi fanno riflettere sull’ampiezza e la vastità della nostra pratica. Tutto sommato con i mantra cantiamo, con la meditazione un po’ preghiamo, alcune sequenze asana sono un vero e proprio ballo… Sempre di più l’aspetto anatomico di questo nervo si avvicina anche a un lato più poetico della pratica yoga.

E da qui, di nuovo, sorge l’importanza di un approccio completo, olistico, verso la pratica. È fondamentale non isolare il momento di pratica, confinandolo a quanto avviene sul perimetro del tappetino, ma estenderlo ben oltre queste frontiere, ma anche, di far entrare quanto c’è fuori dal tappetino sul tappetino stesso. Lo yoga diventa così un sistema completo di stimolo-risposta-stimolo-riassestamento-stimolo-risposta che può continuare all’infinito. Grazie anche, al nostro nervo vago!

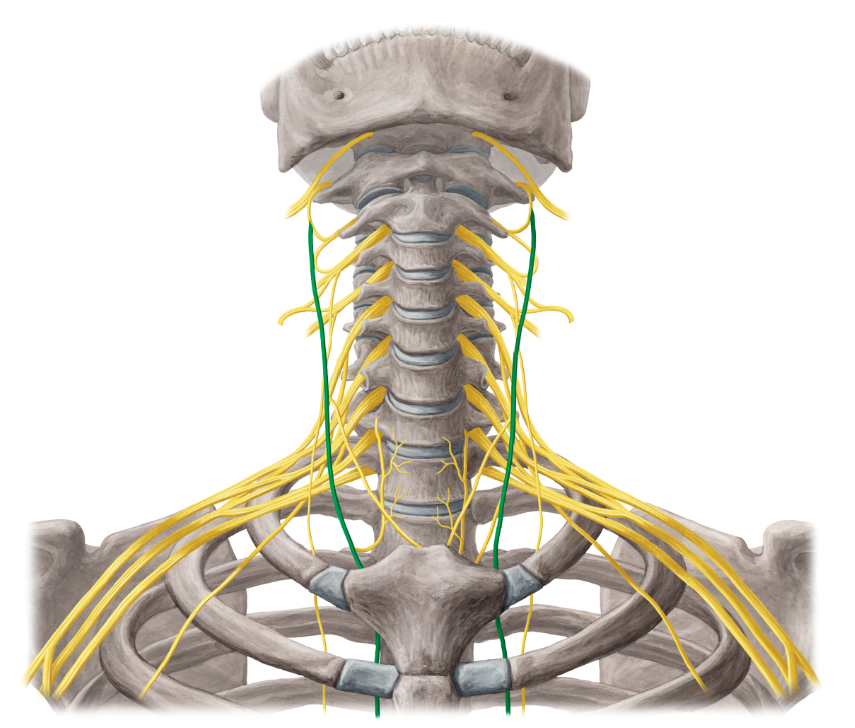

Tra l’altro, ed è da qui che è nata l’idea di questo blog, sull’illustrazione 2 si vede l’origine del n. vago nel collo. Un paio di settimane fa ero a un workshop del mio maestro, che solo al volo ha menzionato il n. vago in relazione alla parte dell’MMMMM in OM. Se il nostro collo, la nostra gola non sono sani ed estesi, il nervo vago è compresso già sin dall’inizio e la trasmissione diventa più difficile. L’importanza dell’apertura e dell’allungamento, ma anche delle vibrazioni di OM e dei mantra diventa ancora maggiore. Spesso, molti di noi sentono un “rilasciamento”, una sensazione di “morbidezza”, di apertura nel petto e nel cuore, grazie ai mantra. Molto è probabilmente spiegabile con lo spazio che si crea per il nervo vago di fare il suo lavoro in pace e poi arrivare a toccare cuore, polmoni e tanti altri organi ancora.

Non sempre le spiegazioni scientifiche sono ben viste in questa pratica, lo so. Eppure per me non tolgono nulla ai multipli livelli magici, misteriosi e profondi che la pratica yoga ha e sempre avrà.

Illustrazione 1 Organi controllati dal nervo vago (in verde))

Illustrazione 2 Origine e passaggio del nervo vago nella gola e petto (in verde)

Note 1- link a diversi studi http://www.huffingtonpost.com/kripalu/yoga-benefits_b_1975025.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3111147/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15750381

ENGLISH

Yoga works. I have no doubt about that. Sometimes I have students who, after a week of intense practice with me during a retreat, are able to alleviate pain that neither traditional medicine nor physical therapy had been able to alleviate.

So, yoga works, but how exactly? In the world of yoga, many concepts are traditionally passed down either orally or in writing in a rather cryptic and incomprehensible way. In reality, there are scientific explanations that help us understand why yoga is so beneficial. And by yoga, I mean a comprehensive approach that includes asana, meditation, and pranayama, not just the physical part. One of these useful “scientific elements” is the vagus nerve. Let's start with a little anatomy. The vagus nerve is one of the longest nerves, originating in the brain and, as its name suggests, wandering throughout the body. It is part of the parasympathetic nervous system (“rest and digest,” the nervous system that makes us feel calm, relaxed, and peaceful), and 20% of its fibers control the organs that keep the body alive (heart, digestion, breathing, endocrine glands), while the remaining 80% is responsible for communication between the belly/stomach and the brain. It is therefore responsible for transmitting all intuitive sensations and “gut” reactions.

When the vagus nerve does not have the “right tone,” many organs in our body and even our mind can be out of balance. A long series of pathologies are attributed to a lack of vagal tone, ranging from headaches and fatigue to gastrointestinal problems, depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. It seems almost absurd that a single nerve could be responsible, or partly responsible, for so many pathologies.

Recently, more and more studies* have been carried out and published that seek to scientifically explain how and why yoga “works,” and many have found a relationship between the practice of yoga and the stimulation of vagal tone. The interesting conclusion is that yoga, more than other physical activities, increases vagal tone. Vagal tone is also increased by many other factors, such as singing, dancing, praying, laughing, receiving massages, but also, for example, through cold and fasting. These are very interesting elements that make me reflect on the breadth and vastness of our practice. All in all, with mantras we sing, with meditation we pray a little, some asana sequences are a real dance... More and more, the anatomical aspect of this nerve is also approaching a more poetic side of yoga practice.

And from here, once again, arises the importance of a complete, holistic approach to practice. It is essential not to isolate the moment of practice, confining it to what happens on the perimeter of the mat, but to extend it far beyond these boundaries, and also to bring what is outside the mat onto the mat itself. Yoga thus becomes a complete system of stimulus-response-stimulus-readjustment-stimulus-response that can continue indefinitely. Thanks also to our vagus nerve!

Incidentally, and this is where the idea for this blog came from, illustration 2 shows the origin of the vagus nerve in the neck. A couple of weeks ago, I was at a workshop with my teacher, who only briefly mentioned the vagus nerve in relation to the MMMMM part of OM. If our neck and throat are not healthy and extended, the vagus nerve is compressed from the outset and transmission becomes more difficult. The importance of opening and stretching, but also of the vibrations of OM and mantras, becomes even greater. Often, many of us feel a “relaxation,” a sensation of “softness,” of openness in the chest and heart, thanks to the mantras. Much of this can probably be explained by the space that is created for the vagus nerve to do its work in peace and then reach the heart, lungs, and many other organs.

Scientific explanations are not always well received in this practice, I know. Yet for me, they take nothing away from the multiple magical, mysterious, and profound levels that yoga practice has and always will have.

Illustration 1 Organs controlled by the vagus nerve (in green)

Illustration 2 Origin and passage of the vagus nerve in the throat